Desmids and fungal parasites

|

|

|

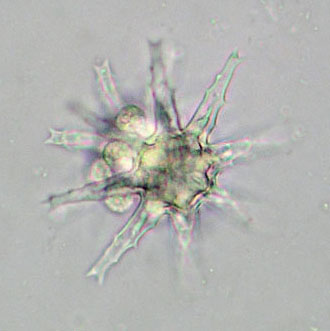

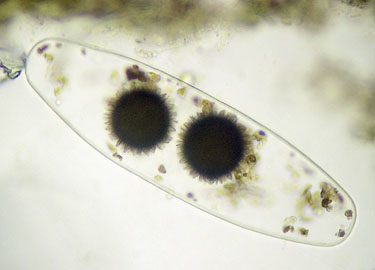

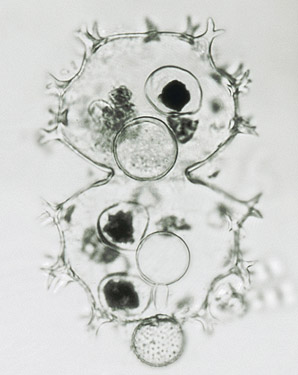

Desmids not only are threatened by predators (like amoebes) and grazers (like water-fleas) but also by parasitic fungi (see Teilingia ). Some species are extremely sensitive to fungal infection, such as the tropical species Staurastrum rotula, complete populations of which often appear to be infested by a chytrid fungus. Identification of fungal parasites usually is very difficult as they but rarely show species-specific morphological structures. Sometimes, however, the relationship between host and parasite is such specific that identification of the host implies identification of the fungal parasite. Aquatic fungi reproduce by means of flagellate spores (zoospores). Based on the number of flagella per spore a commonly made difference is that between monoflagellate fungi and biflagellate fungi (Canter-Lund & Lund, 1995). The thallus (plant body) of a monoflagellate fungus (or chytrid) is most simple, i.e., a single protoplast that, after a period of growth, becomes a sporangium and divides up into zoospores. If a motile, naked zoospore meets a susceptible algal cell it may attach to the cell wall, encyst and subsequently produce a fine germ tube that penetrates the algal wall. Enzymes produced by the chytrid break down the content of the algal cell which is then transferred back into the encysted spore. As a result, the latter enlarges and eventually in its turn becomes a sporangium. For that matter, infection by a single chytrid not necessarily needs to lead to the death of the algal host cell. |